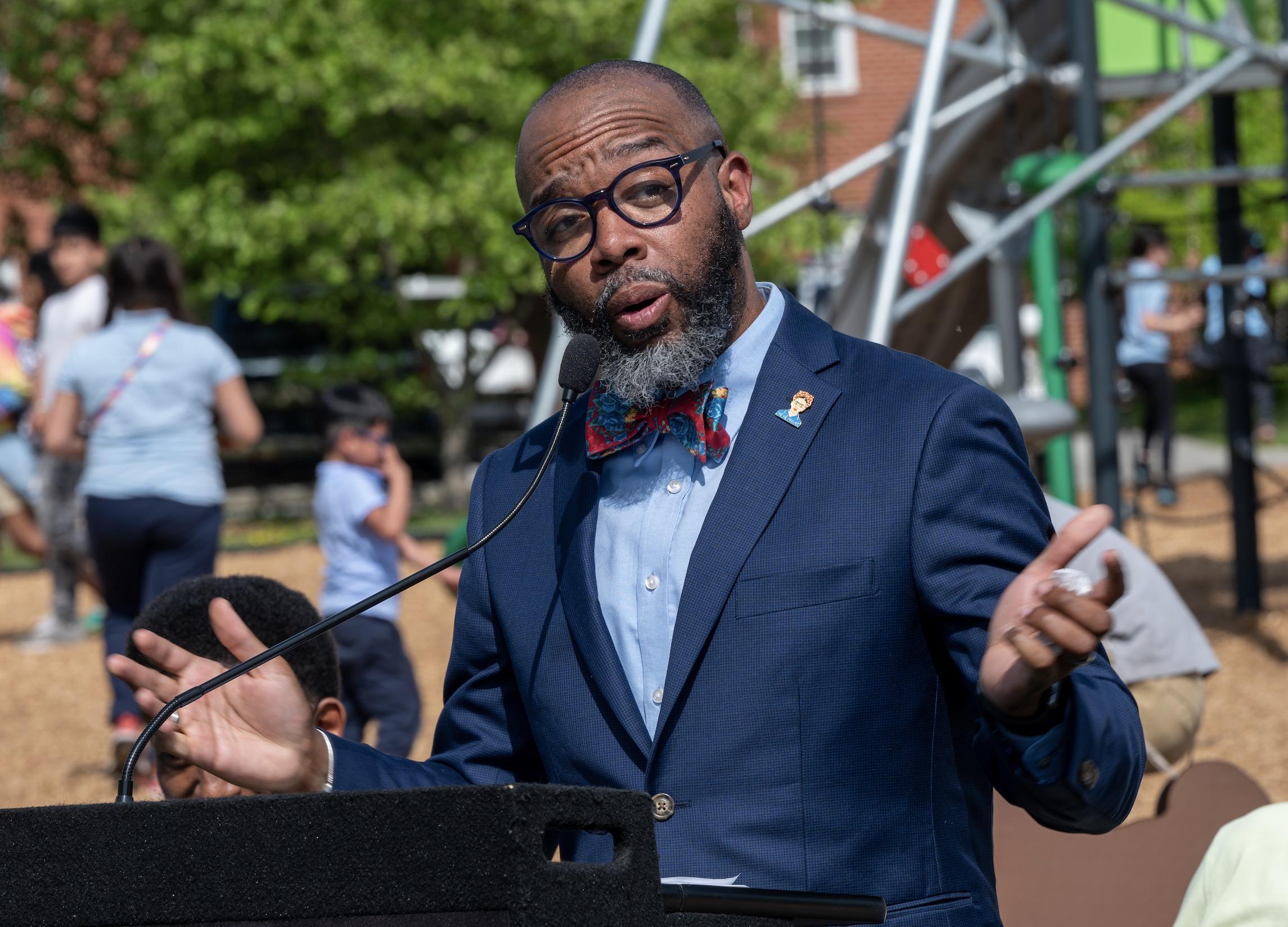

“Who are you?” a 4-year-old boy asked Sedrick Smith when he and his little classmates entered the principal’s office on a recent pre-K tour of Fallstaff Elementary/Middle School in Baltimore.

In addition to being principal at Fallstaff, Dr. Smith is an adjunct professor of education at Loyola University Maryland and a writer who has been published in The Baltimore Sun, the Chicago Tribune and various scholarly journals.

The little boy’s teacher replied, “He’s the boss of the whole school.”

Dr. Smith, a member of Public School Administrators & Supervisors Association of Baltimore, AFSA Local 25, laughs over the memory and adds, “I think of being the principal like being the teacher of a very large classroom.”

Teacher is perhaps the most fundamental part of who he is after teaching 17 years at Baltimore City College High School (known locally as “City”). His subjects included IB World History and History of the Americas.

Given his background, he didn’t think he would go to college, let alone teach. His father earned his diploma at night school; his mother worked in a bakery. But he had motivating teachers in his 4th and 5th grade gifted programs—and one of them, Ms. Scrivener, had discussions with his mother that led him to move on to the prestigious Baltimore City College High School, the third-oldest public high school in the country where mayors and governors had studied.

After graduation, Sedrick began his college years as a broadcast journalism major at Syracuse University. He also took a history course, igniting a love of history—which he instantly equated with storytelling. Not long after, he transferred to Loyola University Maryland in Baltimore to be closer to home and became a history major. Later, in need of money to support his family, he joined the Baltimore City Teaching Residency, a program that recruits, trains and certifies teachers.

Thanks to Cindy Harcum, one of his high school teachers, Sedrick found his first teaching job at his alma mater, and he rose to become chair of the social studies department, director of admissions and teacher leader at City. The story aspect of history is appealing to students, he says, and certain perverse details “always grab them”—like the terrorist Serbian Black Hand’s assassination of Austria’s Archduke Franz Ferdinand, followed by the terrorists’ failed attempt to take their own lives because of a bad batch of cyanide.

History in the making was also part of the experience, including when 18-year-old Michael Brown was shot by a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014, and 25-year-old Freddie Gray was killed in police custody in Baltimore in 2015. Dr. Smith canceled his class when Brown was killed and instead held a student forum with some colleagues in the library. He shared his fears about having a Black son in middle school. “I needed them to know I was hurting in the same way they were,” he says. “It was one of the most powerful days I’ve had as an educator.”

In elementary/middle school, social studies teaching is also a priority. It is taught from pre-K through 8th grade, with standalone classes in 6th to 8th at Fallstaff.

“Social studies is in the political crosshairs today,” he says, “but it’s the linchpin of what makes an informed citizen.” Downplaying or eliminating it in schools is “super dangerous,” Sedrick adds, “leaving us with people who are easily manipulated,” sometimes developing racially charged positions. He wants to make sure “we have good social studies in every school I’m connected with.”

He is greatly encouraged when he walks into Fallstaff, where 62% of the population comes from Spanish-speaking families, with Arabic speaking and Pakistani students starting to enroll. Sedrick applauds “the great interaction among our students no matter where they’re from.”

Nevertheless, there is no shortage of challenges at Fallstaff. Given his school’s population, building community is crucial, not just for dealing with post-pandemic learning loss and face-to-face resocialization, but with matters as basic as addressing required immunizations when many families are afraid of entering government facilities or are without health insurance.

“We always try to bring the community to us,” he explains. “We brought local partners into the school to immunize our families right here.”

“Being a principal has so many layers” that he finds himself leaving the house at 5 a.m. and sometimes not returning until after 8 p.m. He says his hours have definitely required patience from his wife Asha, twin daughters, Audrey and Abigail, and son, Noah, in his first year at Morehouse College. “It’s a struggle turning it off,” he admits, but he has returned to the gym for exercise and private time early every morning. He also continues to coach lacrosse for the City championship girls’ teams, and he watches sports whenever he can: “If there’s a ball involved, I’m into it.”

But much of the time, he is still thinking about teaching. He’s a “teacher principal” at heart. He says, “I miss teaching and I think that’s why I still do the work at Loyola. The adults become your students. But I’m burning up to be in front of kids.” At the moment, a social studies teacher is out on leave and he is putting together a plan to teach the class himself.

“There’s nothing like the feeling you get when you see information click in the minds of a student….it’s like a runner’s high.”